It seems rudimentary: make a good first impression.

After all, the human mind is quick to make judgments on attractiveness, likability and trustworthiness within seconds of seeing someone for the first time, creating cognitive biases that may distort our perception of behavior, according to a study by Princeton University professor of psychology Alexander Todorov.

This psychological phenomenon is present when grading students, for everyone is affected by cognitive biases, necessitating fairer grading methodology, such as anonymous student grading and a transition to online-based assessments.

With respect to student grading, phenomena known as the horns and halo effect are especially at play, processes in which perceived redeeming or negative aspects of people can misleadingly compel us to cast one’s character as favorable or unfavorable, according to Oxford Reference.

“When you’re grading, whether it’s writing in particular, there are biases that enter subconsciously regardless,” social studies Shameemah Motala said. “Let’s say there’s a student that I know and participates a lot in class and verbalizes [content], but then I read their paper, I’m like, ‘I know they knew this.’ I may be willing to overlook some minor details.”

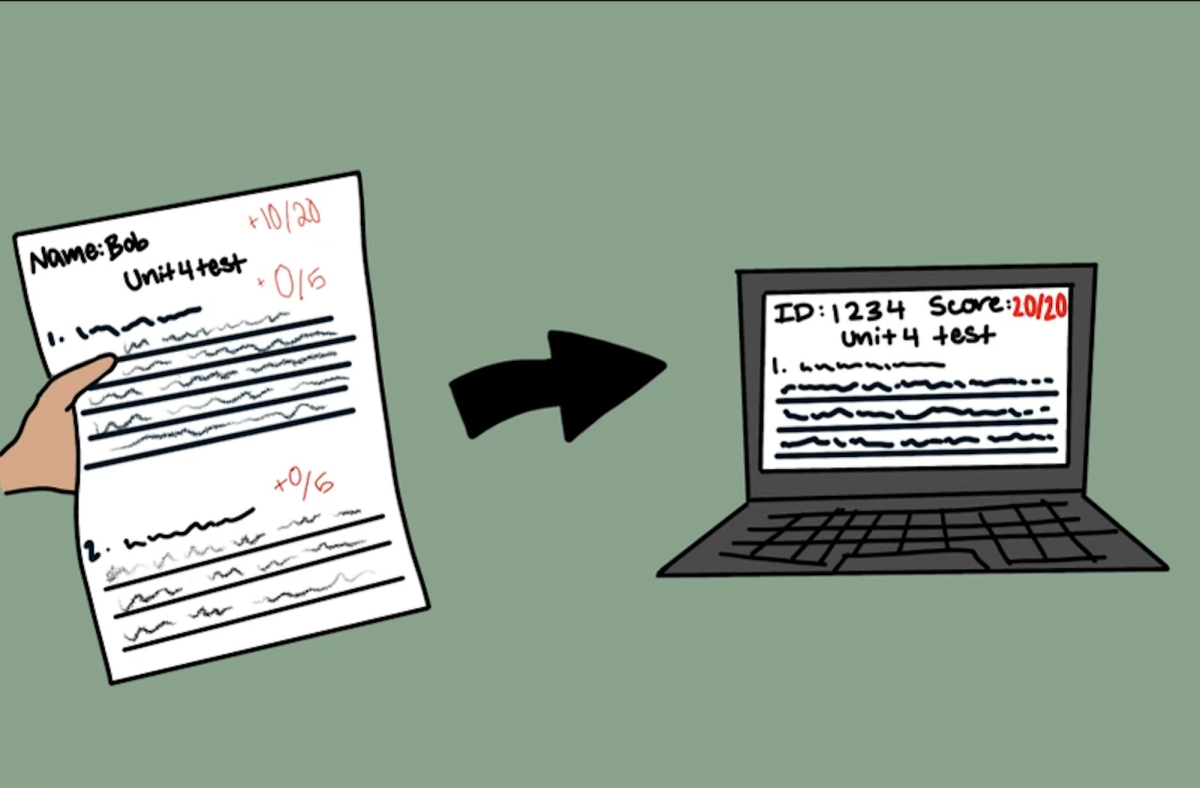

Motala has taken the liberty to have students write their four-digit student ID number in place of their name on free response question assessments, something teachers should consider implementing to ensure more impartial grading practices.

Science teacher Michael Tang, in addition to other AP Biology teachers, have used a similar technique in which four-digit student ID numbers are used in grading, only for him, it is with peer grading.

“If you do peer grading, you’re subjecting students to [shyness, anxiety, and embarrassment], so to eliminate that, we do anonymous grading,” science teacher Michael Tang said. “We use IDs because I don’t know everyone’s ID number, and we swap classes so that you’re grading someone from a different class. So it adds all these different layers of protection for the student’s identity, and it also helps students who are peer-grading to be more objective.”

Furthermore, the horns and halo effects are especially prevalent in handwritten assessments. Research from the National Library of Medicine finds that legibility exerts a bias on evaluation of content and author abilities, demonstrating a strong correlation between handwriting legibility and higher marks.

As such, teachers should do their best to transition from handwritten assessments to online ones, essentially eliminating the handwriting effect. However, AP classes that are preparing students for handwritten AP exams, should be excluded from this.

Of course, with the advent of technologies like ChatGPT, it is not uncommon for teachers to fear cheating and plagiarism, two completely pervasive issues. With this in mind, teachers can take advantage of district Chromebooks that hold lockdown browsers, as used during CAASPP testing, to prevent cheating.

At the end of the day, it is up to teachers’ own volition whether they choose to implement these grading practices or not. With Portola High’s exceptionally talented teachers and coherent grading practices, it is unlikely that unconscious biases play as large a role in grading—but why not play it safer?