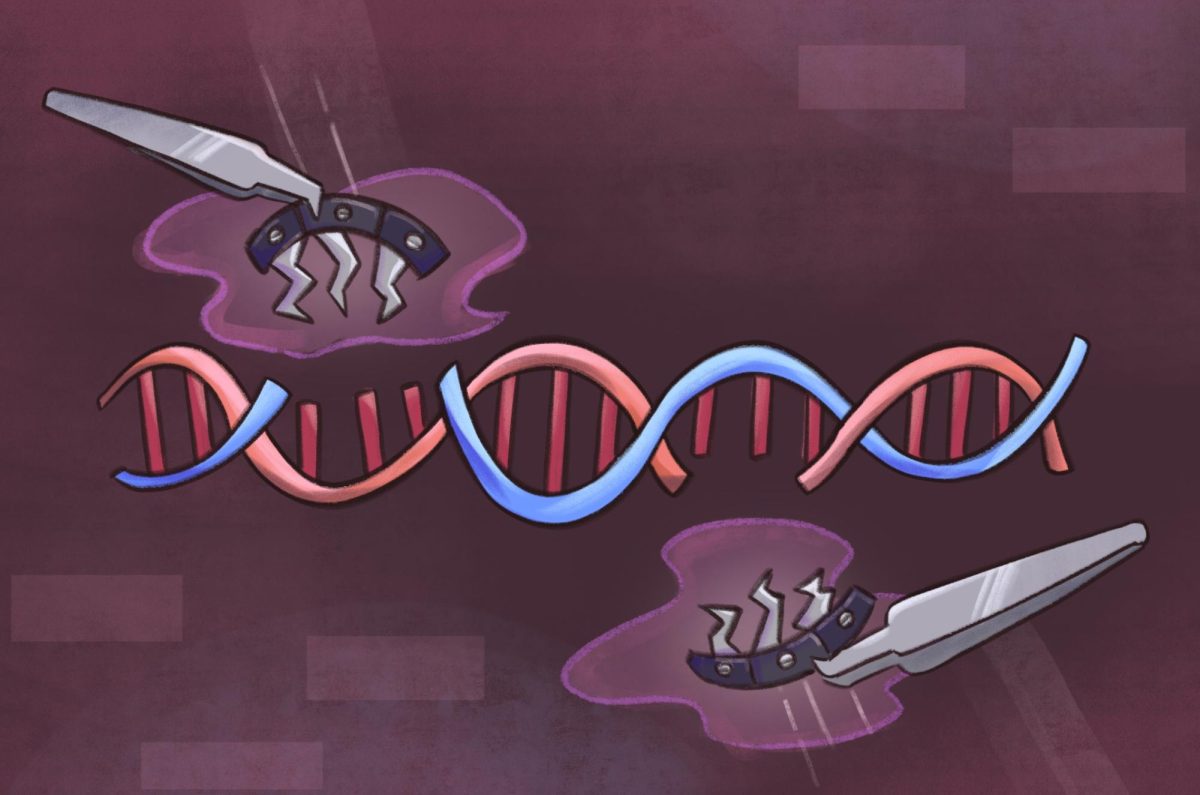

What if you could choose your baby’s eye color? What if you could make them resistant to future HIV infection? Editing a human embryo is just one of the many implications of gene editing. Breakthroughs in CRISPR–Cas9 technology in 2009 enabled the correction of mutations that result in certain diseases, according to the National Institutes of Health.

Yet even with the innovative prospects of such powerful tools, gene editing is complex and dangerous. Such technology should be globally banned in humans by the World Health Organization due to its questionable ethics and risks of abuse. Currently, there are no laws preventing private companies from germline gene editing, according to the Global Gene Editing Regulation Tracker.

The power of CRISPR to eliminate certain genes draws a thin line between treating disease and ridding society of what is deemed a “defect.” After all, what truly merits an elimination-worthy gene? Using CRISPR to remove these diseases poses the harmful idea that these genes inherently taint the human genome and should not be passed on.

“It’s a slippery slope,” senior and Biology Olympiad club president Jeremy Chae said. “Because it really leads us down trying to edit all what we might see as abnormalities or disorders.”

These ableist ideas that pervade the discussion of gene editing also relate to eugenics, or the idea that reproduction should favor “desirable” traits in order to improve the human race, according to Nature. Similarly, using CRISPR to treat disease or edit embryo genes would eliminate those who are classified by society as genetically inferior.

There is no doubt that gene editing has its value, however. It’s logical that most parents would want to prevent their children from having major medical conditions that could ultimately cost more time and money than the technology, according to science teacher Courtney Moder.

The World Health Organization even recommended gene editing in 2021 to target genetic disorders through gene therapy, including treatment of HIV and sickle-cell disease.

“If you can keep a baby or human or somebody from having [genetic disorders] in the first place, I think it’s appropriate, especially if it’s a severe medical condition,” Moder said. “I think it’s gonna be a great tool, a research tool to explore more into some of these genetic diseases and things that we have to help people who are suffering.”

But gene editing carries its own health risks as a novel and developing technology that is consistently in clinical trials. Testing with CRISPR both increased the chance of DNA arrangements that could trigger cancer, according to the Boston Children’s Hospital, and caused cells to lose entire chromosomes, according to Cell Press.

To use such risky technology on unborn children is wildly dangerous; genomes are not objects to be spliced and mended.

Ultimately, the human genome is a conglomeration of diversity. Every unique individual stems from an extensive pool of variety, accumulated over hundreds of thousands of years of mutations and gene flow. While CRISPR offers the tantalizing opportunity to edit away genetic conditions, the technology should be restricted because it reduces human diversity and promotes ableist ideas along the way.