National Discussion Continues as Harvard Court Case Closes

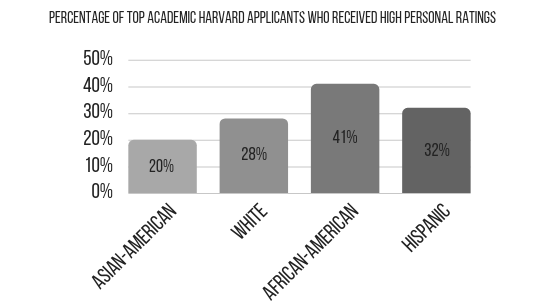

The plaintiff argues that the percentage of high achieving Asian-American students receiving a high personality score is extremely low compared to those of other races, according to NPR.

After three weeks of Harvard students and teachers taking the witness stand in the Boston federal court, the trial came to an end on Nov. 2. With the end of the trial comes the possibility of changes to the current affirmative action procedures in order to ensure equal opportunity for all in college admissions.

Affirmative action originally started as an executive order by former president John F. Kennedy in 1961 to prevent racism in the workplace. It prohibited discrimination in employment, but over the past 57 years, affirmative action has evolved to prevent race imbalances in college admissions, according to Cornell Law School.

At the center of the protests and uproar is the question of race’s role in college admissions. Students for Fair Admissions (S.F.F.A.) is arguing that Harvard is requiring higher standards from Asian-American applicants in order to be admitted. Despite having exceeded academic and extracurricular expectations, Asian-Americans consistently scored lower in terms of “personality,” as rated by Harvard’s admission counselors.

“The plaintiff’s (S.F.F.A.) analysis shows Asian-Americans routinely perform better in academic and extracurricular ratings in this system, but they consistently fall behind other ethnic groups in what is known as a ‘personal score.’ When plaintiff’s experts limited their analysis to only include top academic performers, the differences in personal ratings became wider,” according to National Public Radio.

Harvard counters that without balancing the amount of each race that is admitted, or by using race-blind admissions, diversity rates would drop severely, with minority groups admitted to Harvard, including African-Americans and Hispanics, being cut in half. Additionally, Asian-American admission rates have skyrocketed in the past few decades, so proving discrimination may be difficult for the plaintiff.

“[Former Harvard University President Drew Faust] denied that Harvard discriminated against Asian-American applicants. She noted that 23 percent of Harvard’s current freshman class are Asian-Americans, up from around 3 percent in 1980,” according to NBC News.

Many universities choose their future students through a process that mirrors Harvard’s; what the final result may be is a change in affirmative action policies, like taking into consideration socioeconomic status. Harvard has already countered this, saying that it would still cause a major diversity gap.

“Considering students’ socioeconomic status instead of race, as the plaintiffs are advocating, would reduce the number of African-American and Hispanic undergraduate students by 1,000 over four years,” Bill Lee, Harvard’s lead counsel, said in an interview with the New York Times.

Judge Allison Burroughs, the district federal judge, is expecting another round of arguments from both sides and additional briefs. Her final decision may be delayed to as late as February, but it could take years for the case to reach the high court if the losing side does choose to appeal the decision.

Your donation will support the student journalists of Portola High School. Your contribution will allow us to purchase equipment and cover our annual website hosting costs.

Helena Hu is the Co-Editor-in-Chief of the Portola Pilot this year. As Centerspread Editor and Social Media Director for the past two years respectively,...