Late Father Influences Science Teacher

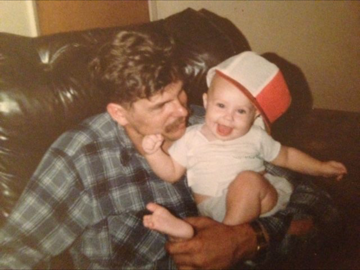

As athletic director and science teacher Katie Levensailor reflects on memories of her dad, her bright blue eyes soften slightly, and she directs her unseeing gaze outward. We get the sense that her mind is a million miles away. Her words, short and stilted, adopt a serious tone, and the room — once filled with light chatter — quiets as she begins her story.

“She never cries,” whispers her wife, activities clerk Alyssa Levensailor. Halfway through, Katie Levensailor pauses to bring over a tissue box for the two of us.

“When he was two years old, his parents abandoned him,” Katie Levensailor said. “These two people who had this farm raised him, and they weren’t very kind to him. They basically just used him to work, so he really struggled in school because he didn’t have a lot of support at home. I think it was sixth or seventh grade when they basically said, ‘You’re not smart, you’re not going to become anything, so you’re not going to go to school anymore. Just stay here and work on the farm.’”

Throughout Katie Levensailor’s childhood, Richard Levensailor strongly supported his children’s education so that they wouldn’t experience the same missed opportunities he did. He worked as a truck driver nearly every day, ensuring that money was never an issue when pursuing her interests in science and sports.

“Because of him, I was able to go to school. If he wasn’t working or driving, I wouldn’t have been able to pay for school,” Katie Levensailor said. “I always reference or think about him when dealing with students and dealing with difficult situations. Everybody has different learning styles and different needs. I know that I want to give everybody that opportunity; I don’t want to be the teacher that robs a kid of their chance. My dad not having opportunities and me feeling like I didn’t want that to happen to anyone else was absolutely a huge factor in becoming an educator.”

Having completed her master’s degree and taught for several years, Katie Levensailor decided to pursue her doctorate in 2015. But within her first year, her father was diagnosed with Creutzfeldt–Jakob disease, an extremely rare and fatal degenerative brain disorder.

“I just remember thinking, ‘If he can do this, I can do anything,’” Katie Levensailor said. “I couldn’t quit, as hard as it was, and my doctorate was hard. But I wanted him to have a doctor. It wasn’t about me. I don’t make more money; nobody cares about titles. It doesn’t mean anything in my career. It was a way of honoring him. Yes, it was hard, and there were times I wanted to quit, but he suffered so badly that I was like, ‘No way.’”

After teaching for six years at University High, Katie Levensailor became a founding educator at Portola High, where she felt the differences between the two schools and the unfamiliarity that came with such a drastic change in environment. An unexpected visit from a simple hummingbird to her classroom assuaged her worries.

“My dad loved hummingbirds. He would sit in the yard and watch the birds, and hummingbirds were his favorite things,” Katie Levensailor said. “It was in the first month of school, we were teaching about photosynthesis, and I was telling this story about my dad and how he was teaching me photosynthesis as a kid. I was telling the story about my dad, and he had just passed away maybe a year beforehand, and a hummingbird was sitting right outside of my window, just buzzing. It really made me go, ‘Okay, I’m in the right place, I’m doing the right thing.’”

Besides the love of learning, her father also imparted on her a strong sense of character and humility, both of which she hopes to instill in her students and children.

“He was super kind. He always saw the good in people, so I try to emulate that. I try to see the good in people,” Katie Levensailor said. “My dad was really giving — things weren’t important to him. I try to put those things in my life, and I try to remember that the material things aren’t important. For me, fancy clothes don’t matter, those types of things don’t matter. What matters is how you treat people.”

Your donation will support the student journalists of Portola High School. Your contribution will allow us to purchase equipment and cover our annual website hosting costs.

Annie Qiao is your 2019-20 Arts & Entertainment Editor for her fourth year at the Pilot! As a passionate admirer of the arts, she hopes to bring a...

Tiffany Wu is your 2019-2020 Co-News Editor! She is most excited to insert ads on Print Days. In her spare time, she can be found browsing memes and eating...