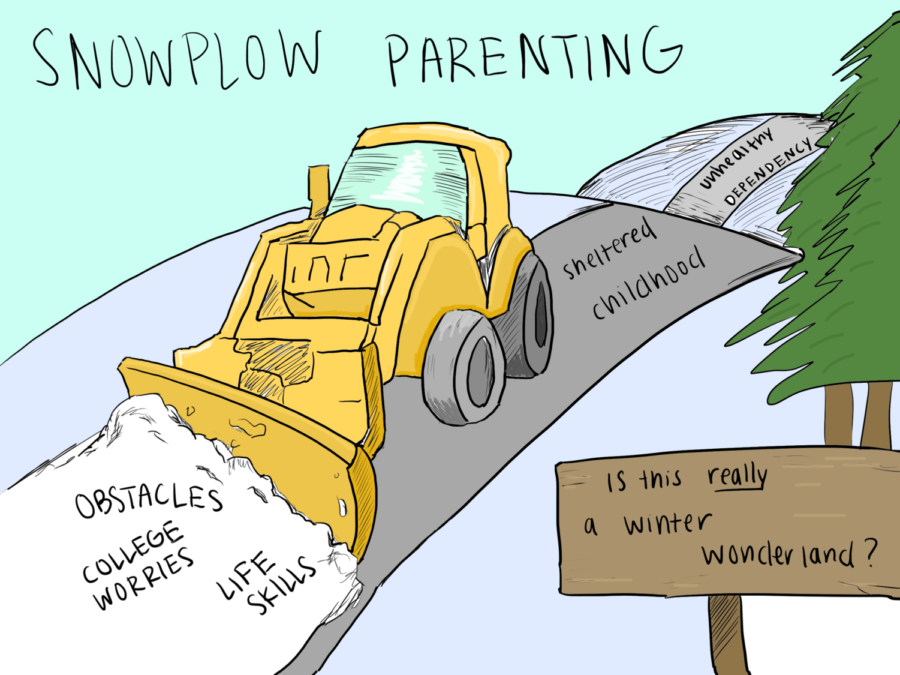

‘Snowplow Parenting’ Leads to Avalanche of Negative Consequences

“Helicopter parenting” of the 1980s has evolved into today’s “snowplow parenting.” Parents, many of whom tend to be of a higher socioeconomic status, often feel the need to clear any obstacles for their children in order to help navigate them into particular goals in the future.

In Irvine, the rise of snowplow parents seems almost inevitable due to the toxic competitive culture, but students can help reverse this process by being more proactive about developing independence from their parents and refusing to shy away from mistakes.

Often, college is the pinnacle of snowplow parenting, and for many, it is the destination and goal for young adults. However, a parent’s hard work getting his or her child into a prestigious university may receive backlash.

According to an article from the New York Times written in March, psychologist Madeline Levine said that she “regularly sees college freshmen who ‘have had to come home from Emory or Brown because they don’t have the minimal kinds of adult skills that one needs to be in college.’”

One example would be a student who did not like to eat food with sauce. Her snowplow parents actively sought to ensure she never had to encounter the substance; at college, she did not know how to cope with the sauce in cafeteria options and consequently dropped out, according to a report from the morning show “Sunny Side Up” on CBS.

The very advantages that parents have tried to pile on students through college counselors, after school activities and summer camps turn into disadvantages when students are unable to function independently as adults.

Because students have always had the path to success cleared for them, they find themselves lost and unable to break that dependency to their parents, which will continue to prevent them from achieving a fuller and more successful adulthood.

For example, in a poll by The New York Times and Morning Consult of a nationally representative group of parents of children ages 18 to 28, seventy five percent had made appointments for their adult children, while eleven percent said they would contact their child’s employer if there was an issue.

The poll provides a shocking look into the negative ramifications of snowplow parenting for their children far in the future, as such parenting prevents their adult children from building essential communication skills.

However, with the Internet at people’s fingertips, a wealth of knowledge is accessible to nearly everyone. For instance, looking up instructions to survive in adulthood, like changing a tire, is readily available. If students today take the time to develop these skills by actively searching online for tools, taking classes or asking trusted adults in their lives, then they will be more prepared for unforeseeable events at college and later in life.

Moreover, a fear of failure is detrimental to children’s futures, because mistakes prove to be infinitely stronger reminders than parents. According to a study published in 2018, students who were given feedback on how to improve from a mistake were more likely to remember the correct answer in the future than students who had made no error at all, which shows the importance of the “productive struggle” essential in the learning process.

One mistake as a child can become a valuable learning experience, and thus, we as a society should try to embrace the exploration of a child’s natural curiosity, even if it may result in failures, rather than forcing him or her to conform to a biased path to success.

That is not to say that parents should not support their children, as summer camps, college counselors or after-school activities can help young adults build personal relationships, develop a stronger character or gain work and volunteer experience.

Overall, however, snowplow parenting can be detrimental to their children as they continue to mature and progress into adults, and it can only be combatted with a change of mindset in both students and parents. Adults must encourage their children to learn on their own and make mistakes. On the other hand, students should take matters into their own hands by taking the time to research and develop important life experiences, whether they are more tangible, like fixing a tire, or abstract, like interpersonal skills.

Your donation will support the student journalists of Portola High School. Your contribution will allow us to purchase equipment and cover our annual website hosting costs.

Annie Qiao is your 2019-20 Arts & Entertainment Editor for her fourth year at the Pilot! As a passionate admirer of the arts, she hopes to bring a...