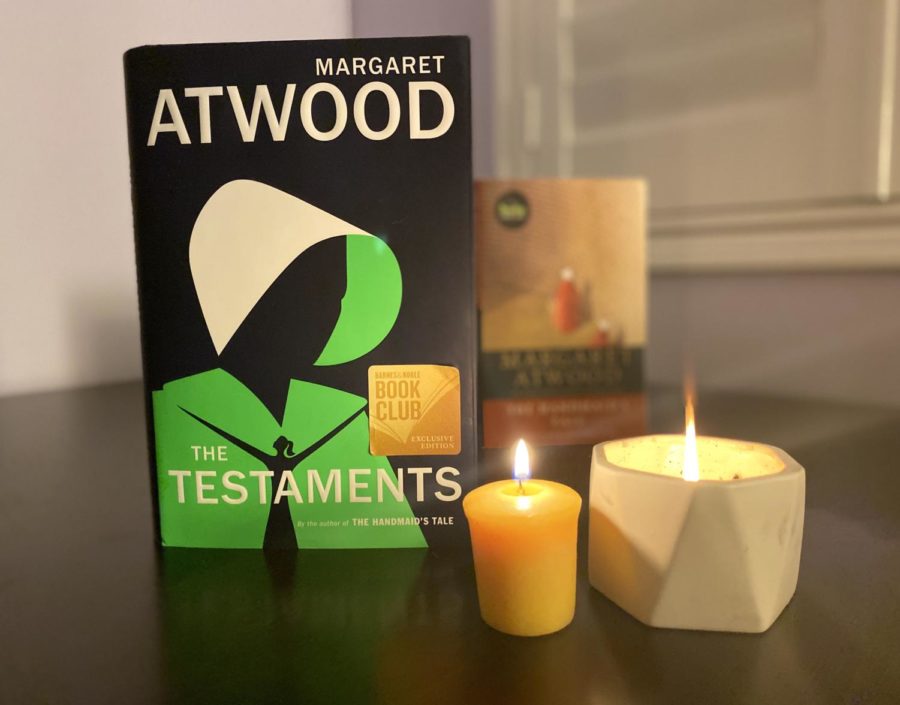

A Review of Margaret Atwood’s ‘The Testaments:’ What Ending Would You Like to Have?

“The Testaments” was among the most anticipated books of this fall, according to Vox, Time and The New York Times, to name a few.

Margaret Atwood’s “The Handmaid’s Tale” was published in 1985 when my mother was a teenager. Its sequel “The Testaments” came out last month; a generation later, the story seamlessly reopens and suggests timeless relevance of the topics of gender, power and faith first explored by its predecessor.

“The Handmaid’s Tale” attracted worldwide attention from the mere existence of such a society as Gilead: the namesake Handmaid has found its way into contemporary culture as a symbol of the #MeToo movement, reproductive rights and feminism. While “The Handmaid’s Tale” focuses primarily on worldbuilding, “The Testaments” focuses on the implications of the society on the hearts of the people.

“The Testaments” features three new voices: two children, Agnes Jemima from Gilead and Daisy from Canada, and Gilead figurehead Aunt Lydia. The new narrators paint a multidimensional and deeply personal picture of Atwood’s dystopian world that fully immerses its readers as stakeholders.

The events of the series center around the theocratic Republic of Gilead, which has overthrown the U.S. government amid a birth rate crisis. In Gileadean society, women are considered nothing more than reproductive vessels and potential temptations to men.

From the society’s unquestioning acceptance that a man’s word is more credible than a woman’s to Agnes’ prelude to her story of sexual assault with, “I can see that it might not seem that significant to some” (96), Atwood provides subtle yet biting commentary on the heartbreaking trajectory onto which our society is heading with gender equality.

As a sixteen-year-old girl, I felt the weight of this book. The constant nagging feeling of “this is not the way things should be” present throughout the novel stayed with me. When I, as the girls’ captain on a cross country team with no female coaches, have to warn my teammates about how to react to men who catcall us during our off-campus runs—is this the way things should be? When I read the news about women who are attacked in public at night, and I wonder why they thought it was a good idea to go out alone—is this the way things should be? Atwood’s story is a reminder that no, even in the world today, this is not the way things should be.

Critics argue that ‘The Testaments” unfolds too cleanly; the combination of a predictable plot and a blaringly obvious ending makes for an unrealistic read. However, the predictability is unavoidable: the labeling of the chapters as “testimonies” already implies the survival and interconnectedness of the characters, and Atwood made it clear before the publication of her novel that its purpose was to explore how a totalitarian government comes to an end. Atwood’s masterful handling of the predictability of her sequel with incremental revelation is what makes it a worthwhile read.

“The Testaments,” with all its questions answered and unanswered cements the series as a classic that—however bleak it may sound—has yet to lose its relevance.

Your donation will support the student journalists of Portola High School. Your contribution will allow us to purchase equipment and cover our annual website hosting costs.

Kate Hayashi is the co-editor-in-chief of the Portola Pilot. She draws all her writing inspiration from Michael Barbaro's "hmms" in “The Daily.” Outside...