Promoting Academic Integrity Through Student Efforts

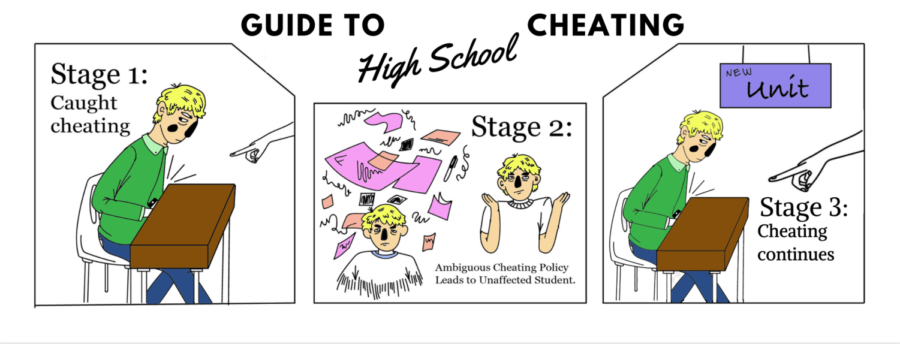

Academic dishonesty often occurs in a cyclic pattern when there is no firm cheating policy in place. With 57% of teachers at IUSD agreeing that cheating is a problem at their schools, a stronger stance from the district is necessary.

Whether a student is copying a homework problem or obtaining a leaked exam key, under Irvine Unified School District’s current academic honesty policy, there is no clear distinction. The policy took effect Apr. 9, 1973 and has not been revised since; only in recent months has the board begun proposals for a new policy in light of cheating occurrences across the district’s high schools in the last several years.

The policy must be changed to clearly outline districtwide consequences for each occurrence of cheating, ideally with a mandatory project and reflection for 50% credit on the first offense, an automatic zero on the second offense and an F in the class on the third offense. Such a policy would enforce the seriousness of cheating while still offering a chance to demonstrate learning. However, in order to truly resolve the issue of academic dishonesty, the district must address the root of the problem—the highly competitive and ultimately toxic academic atmosphere characteristic of Irvine—and reassess the way intrinsically versus extrinsically motivated students are rewarded by this system.

The original policy dictates that “consequences for dishonest behavior shall be based on an evaluation of the specific situation, shall be logical to the offense, and shall be commensurate with the seriousness of the act and the previous record of the student.”

While this policy provides a loose guideline, the exact repercussions are left to the discretion of the teachers on a case-by-case basis. For many teachers, this means spending hours creating different versions of tests and assignments in an attempt to circumvent cheaters.

“It needs to be more work on the student than it is on the teacher,” academic honesty committee member and science teacher Sharon Fronk said. “It takes me about two, maybe three hours to make a test and all its different versions. I’m not going to spend another two hours for one kid that cheated to make a test for them.”

Teachers and students alike identified a rise in academic dishonesty at their schools in the district-wide annual survey last year.

“Teachers reported at a 57% rate of agreement at the high school level that academic honesty was an issue and students across grades 3 -12 agreed at a 28% rate,” according to IUSD secondary education executive director Keith Tuominen.

According to a Rutgers University case study by Donald McCabe, Linda Trevino and Kenneth Butterfield, “Empirical research has found an inverse correlation between integrity policies and instances of academic dishonesty.” In order to reduce instances of cheating, district policies must “clearly communicate definitions and expectations regarding academic honesty… and create an environment in which academic dishonesty is socially unacceptable.”

Facing academic repercussions can dissuade immediate cheating. However, a system of brute punishment such as an automatic zero would be counteractive, as the student has still not actually learned the target content; using a three-offense system allows them to learn the material and prove that they are willing to work with integrity in the future. Our three-tiered proposal of consequences is firm enough to curb serious instances of cheating while not devastating the prospects of students with genuine intentions to learn from mistakes.

The academic dishonesty problem is part of a fundamental lack of intrinsic motivation to learn that must be resolved first. The focus on grades and college admission has forfeited the meaning of learning wholly for the sake of learning. While it is unrealistic to expect students to detach meaning from grades, it is necessary to reevaluate what it is exactly that good grades are rewarding.

Even outside of Irvine, high school has lost its meaning as a place for learning in its own right and become a mere stepping stone toward the ultimate goal of getting into a “good” college.

As journalist Vivian Yee writes in the New York Times, “All this makes for a culture in which many students band together, sharing homework and test advice in a common understanding that they simply have to survive until they reach their goals: dream colleges and dream jobs.”

Some students share the sentiment that it is easier to cheat to benefit their grade short-term than put in the effort for studying to gain long-term knowledge. This toxic mindset is reinforced by a grading system that rewards performance at the cost of integrity. When students evaluate the cost-benefit ratio of the risk of cheating, academic dishonesty becomes justified in students’ minds as a beneficial choice in the path towards college rather than a moral wrongdoing.

“Since we’re so competitive and so driven by academic success, the thought of failure is genuinely terrifying,” sophomore Madeleine Young said. “When students feel unprepared or burnt out, the fear of failure outweighs their logical thoughts.”

Students need to realize that they are in control of their grades purely through their efforts and abilities, not their capacity to manipulate the system through dishonesty. This is only achievable through a classroom environment that encourages growth and a grading system that reflects the achievement of these goals.

According to Lori Kay Baranek in her study “The Effect of Rewards and Motivation on Student Achievement,” “There is a need to train teachers in how to teach students so that they become intrinsically motivated, instead of just propelled along by the vision of the next external reward. The key factors are to create an autonomous classroom environment, and to teach students to perceive themselves as decision makers.”

In order to more aptly address this issue of a toxic academic culture, the district should implement our policy which will help prevent more instances of cheating without crushing the individual’s motivation to continue to learn. By having a three-tiered system that encourages academic progress rather than harsh punishments to each student, students will be given multiple opportunities to learn from their mistakes. As evidenced by multiple researchers, providing students an opportunity to learn from their mistakes allows the potential for them to continue to learn, the ultimate goal of school itself.

Your donation will support the student journalists of Portola High School. Your contribution will allow us to purchase equipment and cover our annual website hosting costs.

Nate Taylor is the 2021-22 front page editor and photo editor. He is ready to improve his design skills and create memorable Portola Pilot front covers....