Setting a Standard: Trying Juveniles for First-Degree Assaults

Youth are often not held completely responsible for their crimes, especially first degree felonies like homicide and sexual offenses. The number of juveniles receiving a life sentence without parole dropped 6% even though the number of serious youth crimes increased by 13% within the past five years, according to New York Times.

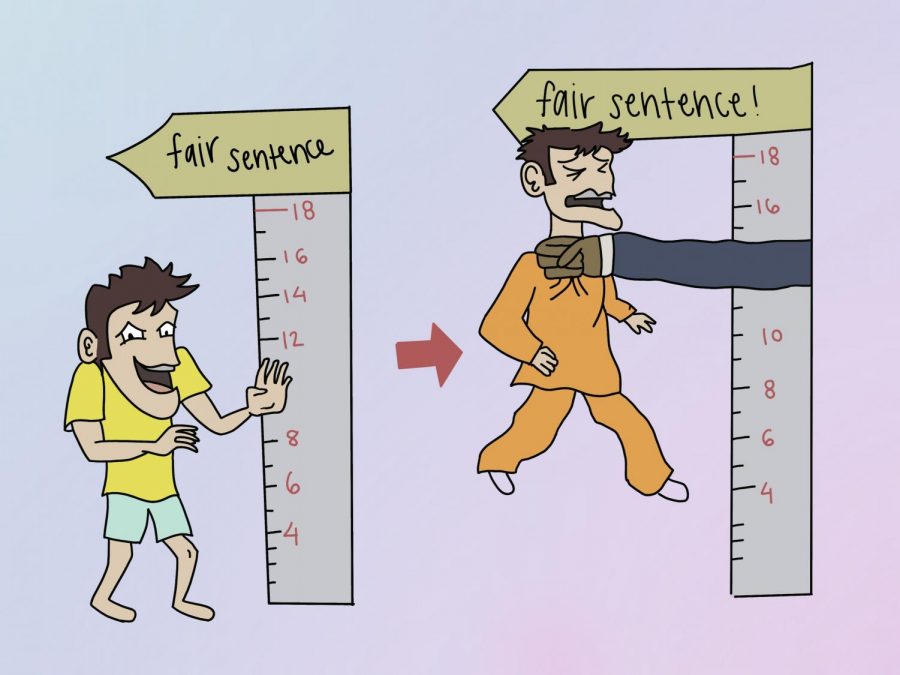

Children are often taught from an early age that actions have consequences, yet our current justice system fails to establish this principle. By treating violent juvenile offenders with disproportionate sentences, the federal court system perpetuates the notion that certain actions deserve lesser punishment, all because of a number.

At some point, society needs to teach all youth that there are actions which are permitted and those that are not under any circumstance. One way that we can begin to teach this lesson is by setting a standard and trying juveniles for violent first-degree felonies as adults.

On Aug. 25, 2020, 17-year-old Kyle Rittenhouse shot and killed two men in Kenosha, Washington and was charged with two counts of homicide, unlawful possession of a firearm and two counts of reckless endangerment, according to CNN. Rittenhouse was charged as an adult despite being a juvenile when he committed the crime, sparking debate over whether or not juveniles should be tried as adults for criminal offenses or if their age should play a factor in sentencing. On Nov. 19, 2021, the jury officially acquitted Rittenhouse of all charges against him.

“In terms of the Parkland shooter or Kyle Rittenhouse, in that extreme of a measure, where you have a suspect who has used a gun, killed people and it’s premeditated — in that case, the courts should consider life without parole,” social studies teacher Natasha Schottland said. “Let’s take Rittenhouse as an example right now: him bringing guns over state lines, that has some sort of premeditation because you have to have thought through what you’re going to do with those guns.”

In serious offenses, most notably first-degree felonies, committed by youth and individuals under the age of 18, it is only fair for the victims if the youth are tried as adults. Despite this, the death penalty should not be imposed on any juvenile or offenders of any kind. In fact, numerous treaties prohibit the juvenile death penalty such as the Convention on the Rights of a Child which only two countries, Somolia and United States refuse to ratify, according to American Civil Liberties Union.

“In extreme circumstances, there’s got to be some accountability,” Schottland said. “People should be held accountable for their actions, but I think there does need to be a little bit of forgiveness if you have juveniles committing those heinous acts just because they’re not fully developed. Their brains aren’t fully developed and, according to the courts, they’re not adults yet.”

However, the adult justice system simply does not have the capacity to respond to the needs of children, especially those who are teenagers, in ways that are developmentally appropriate.

Since the prefrontal cortex, the part of the brain responsible for decision-making, is still developing in adolescents, they rely on the amygdala to make decisions and solve problems more than adults do. This part of the brain is associated with emotions, impulses, aggression and instinctive behavior.

Therefore, by nature, they generally tend to make impulsive or harsh decisions, according to the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry.

However, despite this, there are certain crimes which juveniles commit that draw into question how safe a community would be if they were to be set free or allowed to serve a reduced or alternative sentence.

Diante Pellum was 14-years-old when he was tried as an adult and convicted of shooting another teen in the back of the head near Federal Way in Washington. Alexander Crisostomo stood trial as an adult for killing a 41-year-old man when he was just 15, according to the Seattle Times.

The average youth sentence in the United States is only 34.6 months, while adults had an average sentence of 141 months, according to Connect Us. Sentencing them as adults gives the justice system the time it needs to offer a true chance at rehabilitation without compromising the safety of the community.

A report by California’s Division of Juvenile Justice found that 74.2% of those released from the juvenile justice system were rearrested within three years of being discharged.

“If it’s a crime like murder, a school shooting or a mass murder, there needs to be consequences,” mock trial member and sophomore Josiah Lee said. “Obviously, rehabilitation would help that person, but regardless of whether or not it’s a mental health issue, that kind of a crime justifies a bigger punishment.”

In the case of violent first-degree felonies, the justice system should try juveniles as adults since these crimes require a uniform punishment regardless of age, creating a measure of consistency for certain crimes. Convicting juveniles with harsher sentences also ensures that violent juvenile crime does not persist and decreases the likelihood of a juvenile committing multiple severe crimes.

Your donation will support the student journalists of Portola High School. Your contribution will allow us to purchase equipment and cover our annual website hosting costs.

Dheeksha Bhima Reddy is the co-Editor-in-Chief for her third and final year on the Portola Pilot. Through her newfound obsession of drinking coffee (cold...

Arnav Chandan is the Sports Editor and Co-Business Manager for his second and final year on the Portola Pilot. Outside of spending hours upon hours in...