Stephanie Zhang Turns Passion into First Student-Made Class

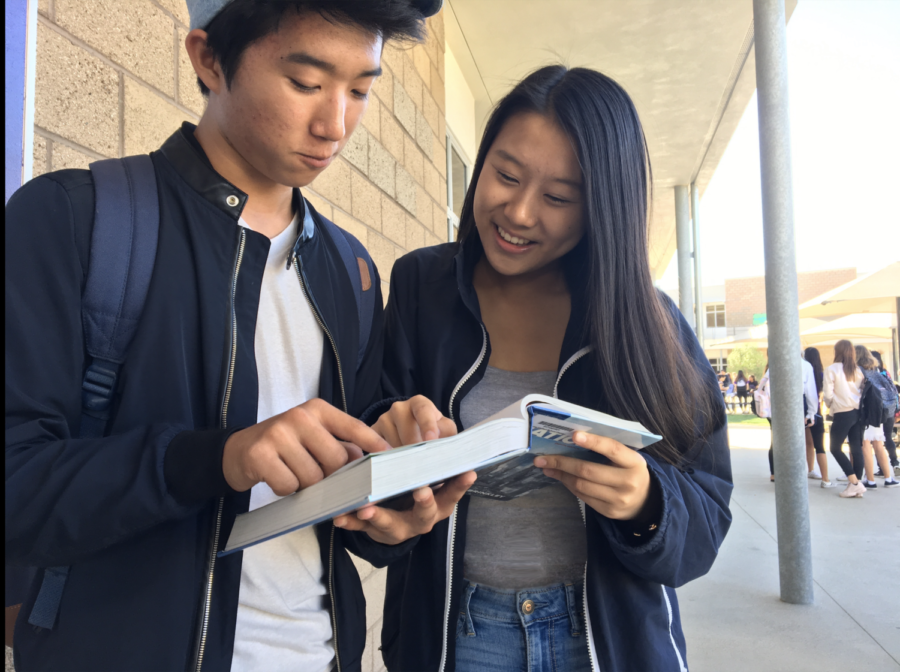

Junior Stephanie Zhang and freshman Ryan Jung, collaborators in developing Portola’s new philosophy class, point out references to philosophical topics in the AP U.S. History textbook.

After cultivating a philosophy club for a year, junior Stephanie Zhang and her devoted team of philosophy fanatics advanced from club founders to curriculum developers as they became the first students to develop a passion course on campus.

As a new school, Portola High is bursting with opportunities for students to become involved in the foundation of its culture and course offerings. Zhang proved this to be true when she found herself leading the groundwork for a philosophy class after a conversation with social studies teacher Wind Ralston.

“I had APUSH (AP United States History) with Mr. Ralston next period, and I found out that he was trying to create a philosophy class,” Zhang said. “I’m the president of Philosophy Club; philosophy is a really big part of my life, and he saw that. We set up a meeting, and that’s how I became involved in designing this course at Portola.”

Portola High’s mission statement, to help every learner “belong, contribute and thrive,” advocates for students to become involved and engaged in their education, which opens the door for opportunities such as this.

“The whole idea at Portola is to give the learners the option of learning what they want to learn, and what better a platform is there than having students help create a class? I can’t think of any better way to empower students at Portola,” Ralston said.

But Zhang and her team of freshman Ryan Jung, sophomore Jamie Shin and juniors Mariya Idris and Nishad Francis, are not just “helping” to create this class. In fact, in this unconventional approach to developing a course, the students are in charge.

“Mr. Ralston gives all the liberty to us,” Zhang said. “The themes that we want to talk about, the structure of the class, how we’re going to grade the projects — all of that is up to me and the team I assembled.”

Ralston mainly serves as a middleman between the students and the administration, making sure that the course fulfills the A-G requirements, the criteria to be recognized as a course students can take to earn credit toward becoming minimally eligible for admission to the University of California (UC) and California State University (CSU). This entails tasks such as providing the team with a timeline for the school year, meeting with staff and administration and approving or rejecting course content ideas based on A-G requirements.

“I have my ideas about how I would want to do it, but this isn’t about me,” Ralston said. “This is about giving them the chance to literally create something at a new school, a course that will last long after their time here.”

Staying true to this vision, there will be no hierarchy of minds in this class. The founding members and Ralston will have the same role as everyone else in the class: to facilitate discussions and contribute ideas. The goal is that Ralston will serve as a guiding hand, but ultimately the students will drive the learning process, creating lessons and developing their own semester-long projects.

“Everyone in philosophy is an intellectual equal. It’s not a matter of who knows more or who knows what or who can argue better,” Jung said. “It’s just sharing your own ideas and having meaningful discourse.”

Zhang has long been a proponent of finding meaning and personal connections with concepts taught in school rather than passively studying for the sake of passing a test. As a student, she knows what her classmates find appealing and engaging, and she knows what might bore them.

This insight allows her to mold the course to ensure that students will be able to truly connect with the content.

“A lot of the times, courses aren’t able to cater to exactly what students would need to thrive because most teachers don’t have direct student input,” Zhang said. “When students are able to design their own course, it’s a progressive step towards learning and educating in a way that would actually be meaningful to each person.”

Each unit, the seminar-style class will focus on a theme like “History of Thought” or “Metaphysics/Ethics,” and students will learn from reading, analyzing multimedia sources such as films and articles, writing, discussing and creating their own lessons.

“During the Enlightenment, they had coffee houses where people would just talk and discuss important ideas like the world, society and humanity, and I want that to be replicated in this class,” Zhang said.

Eventually, the team’s work and development will culminate in a semester-long course that will be offered next school year.

Your donation will support the student journalists of Portola High School. Your contribution will allow us to purchase equipment and cover our annual website hosting costs.

Kate Hayashi is the co-editor-in-chief of the Portola Pilot. She draws all her writing inspiration from Michael Barbaro's "hmms" in “The Daily.” Outside...