Colleges Are Going Test-Optional, but Students Need To Play It Safe

Students who choose not to prepare for standardized tests may face heightened pressure to take the tests in their senior year, especially if colleges opt for a test-mandatory policy following this admissions cycle.

In response to SAT and ACT testing centers shutting their doors across the nation due to COVID-19, more than 1,500 colleges across the nation are making these standardized tests optional for first-year applicants enrolling in 2021. Yet, banking on the unprecedented nature of the pandemic to permanently shift how admissions offices operate is an ill-conceived strategy and can lead to unnecessary stress if students put off test preparation until senior year.

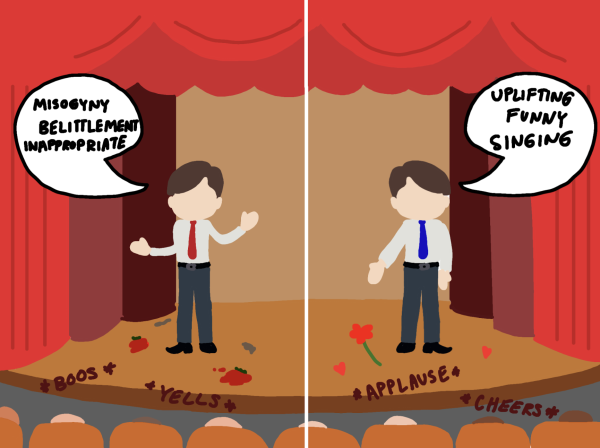

It is important to note that most schools have long used the holistic review process summarized by the College Board when considering applicants, meaning that admissions officers evaluate the “whole” applicant. This means that test scores are not weighted like entrance exams; rather, they are a piece of a larger puzzle that completes an applicant’s profile — a finding that can be glimmer of hope for students who squirm in high-stakes testing environments.

Most schools are happy about this. It’s not only one less thing for them to look up, but it also allows them to focus on what they really like.

— Maxine Seya, founder of SocratesPost

What’s more, going test-optional seems to be catching on. SocratesPost, an independent college admissions publication, has interviewed college admissions officers about test-optional policies since 2018. With test-optional policies experiencing a peak this admissions cycle, founder Maxine Seya has seen greater leeway in the admissions offices of small liberal arts colleges like Carleton College, located in Northfield, Minnesota, all the way to the University of California system that houses hundreds of thousands of undergraduates.

“Most schools are happy about this. It’s not only one less thing for them to look up, but it also allows them to focus on what they really like,” Seya said.

Even so, testing requirements varied widely across schools pre-COVID. For example, the University of Chicago has been a test-optional school well before COVID-19, while Georgetown University’s admissions office strongly recommended applicants to take additional SAT Subject tests in years past.

If students do not have test scores to submit, the burden falls on them to communicate with admissions offices about any extenuating circumstances that left gaps in their applications.

“With the UCs, they need to be consistent across the board… With private schools, it’s a case-by-case situation,” counselor Nicole Epres said. “You can really plead your situation to the admissions readers and be like, ‘Given these external factors, I was unable to take a test.’”

While admissions requirements appear stringent at face value, the holistic review process can do much to offset a discouraging test score.

“[Admissions officers are] not in the business of rejection; they’re in the business of admission,” Seya said. “They want to find reasons to admit you… They’re serious when they say that they don’t need test scores.”

Junior Howard Zhang, who completed the standardized testing journey in his sophomore year, said he believes students should begin studying as soon as the pandemic shows signs of subsiding.

“We probably won’t be able to take the ACT for as long as there’s no vaccine,” Zhang said. “Start studying around March or the beginning of summer.”

Until admissions offices come to a consensus that standardized tests are no longer mandatory, students must continue preparing for these tests if they want to take full control of their application process. Without adequate preparation, students may see admission requirements working against them, forcing them to pare down their college lists to only a handful of schools.

Your donation will support the student journalists of Portola High School. Your contribution will allow us to purchase equipment and cover our annual website hosting costs.

Ryan Jung is the co-managing editor of the Portola Pilot. He is looking forward to working in the newsroom three times a week and communicating with Pilot...

Nate Taylor is the 2021-22 front page editor and photo editor. He is ready to improve his design skills and create memorable Portola Pilot front covers....