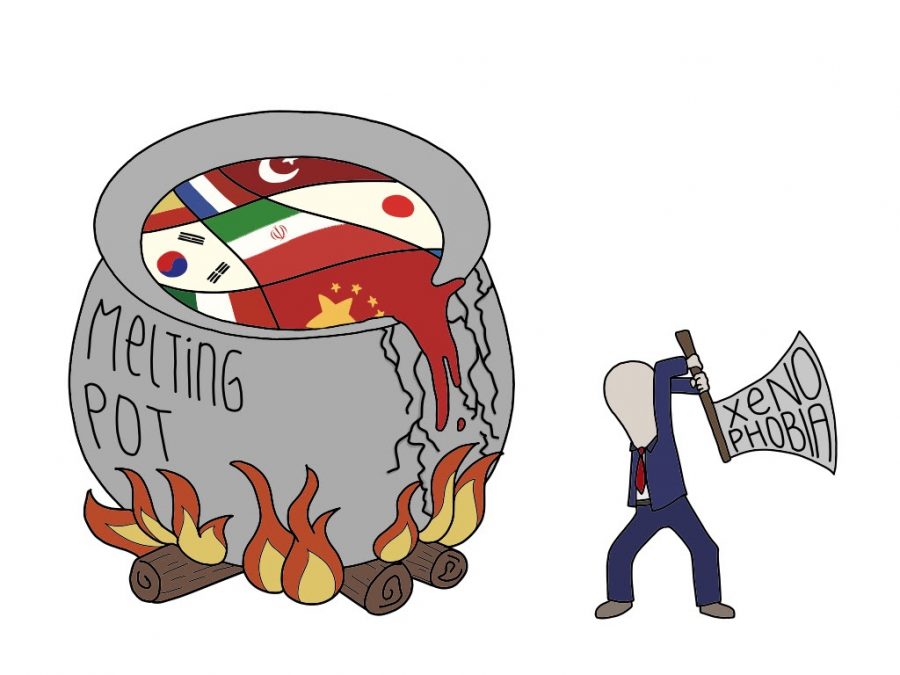

Much More Than Sticks and Stones: The Trump Administration Contributes to Xenophobia

U.S. leadership’s irresponsible depiction of the Coronavirus has divided the nation, putting a target on the backs of Asian Americans.

No, “kung-flu” is not a distasteful punchline from an outdated comedy or offensive historical cartoon. Believe it or not, it recently came from the mouth of a White House official and is among several of the COVID-19 misnomers that President Donald Trump and his constituents have used since the outbreak’s conception in March 2020.

In a society that has proven to act with shrouded impulsivity in the face of chaos, leaders and representatives of this nation must quell the fear they have incited with their misleading word choices and reform the rhetoric they use.

With existing accusations of xenophobic language on Trump’s Twitter, a journalist’s photo capturing that the president had used marker to replace the “Corona” in “Coronavirus” with “Chinese” on a press conference speech script fed the controversy. When faced with inquisition during a later press conference, Trump dismissed reporters’ concerns of instigating racism, claiming to honor the accuracy of China as the virus’ origin.

The contention of this issue is not whether the first case of the virus began in China; rather, it is the insistence of influential figures to racially-characterize a deadly virus.

On May 2015, Assistant Director-General for Health Security at the World Health Organization (WHO) Dr. Keiji Fukuda advised scientists to be mindful of unintended repercussions upon nations, economies and people when establishing names for diseases.

“We’ve seen certain disease names provoke a backlash against members of particular religious or ethnic communities, create unjustified barriers to travel, commerce and trade, and trigger needless slaughtering of food animals,” Fukuda said in her letter featured in Science Magazine. “This can have serious consequences for peoples’ lives and livelihoods.”

Using “Chinese virus” for the sake of accuracy is not only misinformative, but also hypocritical. Its users are blatantly refusing the official, scientifically-established name: COVID-19. It merely supports an agenda that aims to scapegoat and alienate an entire demographic.

With a misconstrued identity of the virus in the media, it is no surprise that anti-Asian sentiment has skyrocketed in conjunction. According to the Asian Pacific Policy and Planning Council, the Stop AAPI Hate reporting center received over 1,100 cases of COVID-19-related discrimination and hate crimes against Asian Americans within its first two weeks of establishment on March 19.

While Irvine residents are constantly reminded of how diversified the city’s large make-up of Asian cultures can be, far more of the nation’s individuals are unable to differentiate between ethnicities. Although China in particular is being associated with the virus, partakers in recent acts of hatred seem to perceive the entire Asian race as monolithic, reducing dozens of cultures into a single deadly virus.

One prime example can be seen in a recent Texas Sam’s Club stabbing attack on three Burmese family members, as a result of the suspect’s assumption that they were Chinese. Even with evidence against Asian heritage as an inherent indicator of contagion, hysteria over the outbreak poses an opportunity to unleash dormant xenophobia.

It all starts with the irresponsibility of leading figures, tone-deaf to the impact of words despite the awareness of their highly impressionable audience. Trump not only must publicly address the harm in his word choice, but should work closely with organizations like AAPI in enforcing preventative measures for hate crimes and defending the voice of Asian-Americans.

Your donation will support the student journalists of Portola High School. Your contribution will allow us to purchase equipment and cover our annual website hosting costs.

Kelthie Truong is a Co-Managing Editor for the 2020-21 school year, her second and final year with the Pilot. When she’s not in the newsroom, you can...

Jaein Kim is the Director of Photography this year on the Portola Pilot. She is extremely passionate about visual media ranging from digital art to videography...